I asked my friend Rebecca Gethin three questions about her recent poetry pamphlet A Sprig of Rowan (Three Drops Press, 2017) . Below are her answers, and two poems which she kindly agreed I could post here, plus images and links.

I asked my friend Rebecca Gethin three questions about her recent poetry pamphlet A Sprig of Rowan (Three Drops Press, 2017) . Below are her answers, and two poems which she kindly agreed I could post here, plus images and links.

1 — ELLY: At the same time I was reading your poems, I was rereading an essay in Jane Hirshfield’s book of essays – Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry about memory and how oral verse was the essential tool for preserving what was important – long before there was reading and writing. She says “ “… every poem remains an attempt to name with fidelity some complex aspect of the human experience and keep it available through time … the art of poetry remains a daughter of Remembrance …”

Does this ring true for you? If so, can you give me an example or two from your poems, of something(s) that you want to “keep available through time”? Why?

1 — REBECCA: As the poems emerged I realised that they were about experiences that had been important for the growth of my psyche. Every poem contains a ‘story’ bigger than myself but every poem comes from a lived experience as well. So a barn owl I saw flying by day becomes a messenger from the underworld, a pony I once encountered on a beach becomes a Kelpie and the village blacksmith of my childhood takes on the qualities of Vulcan: I remembered my sense of terror and wonder as he shod horses among the flames with the noise of hammering and the bellows and that they submitted their power to him so easily. I knew these islands of poems were linked organically like an archipelago when they all slotted into their places so easily.

2 — ELLY: When reading A Sprig of Rowan, I started thinking about the use of mythology in poetry – or not to get hung up on labels – legends, tales, or storytelling in general. I came upon this blog post by Reginald Shepherd . He talks about the various functions myths can serve in poetry: for example, they can simply create a fun or intriguing story , but they also help to “reconcile us to tragedy and other painful events, they help us to deal with the intractable fact of death, and they project human fears, hopes, and desires outward into shapely figures and coherent narratives.”

Your poem “Dulsie Bridge” is, for me, an example of a “shapely figure” and a “coherent narrative”. Can you tell me more about the background to this poem?

2 — REBECCA: “Dulsie Bridge” is the poem that includes the key of the title. As a student I worked in a Scottish shooting lodge for two summers. I was friendly with this dear lady who lived nearby and who plucked all the birds they shot. It made her weep. She lived in the tiny croft with an outside loo called Dulsie Cottage (near the famous bridge of that name) where she had indeed raised many children and a couple of extras too. She told me often that she was more afraid of the fairies getting into her house than of any stranger (she owned nothing of value) and the only thing that kept them away was a rowan sprig in the lock. She was really a good fairy herself living in a bygone age when people believed such things. She made me feel the old ways still existed and that this would in some way, as you mention this, keep me afloat during life’s ups and downs so long as I kept believing in the sprig of rowan.Years later, I went back to find her and she gave me tea and sandwiches. After that I heard how although she had cancer she still rode around Nairn on a bike visiting old folk. One of her younger sons supplied logs to my mother-in-law coincidentally. So this poem is a fun story but also a significant one for me.

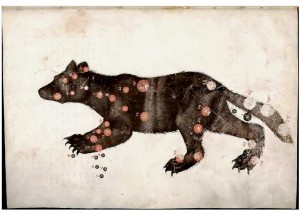

How do you see any or all of these methods/ intents in A Sprig of Rowan? I am in awe of your Dartmoor Princess 5-poem sequence which is based on a discovery [Links: BBC: ‘Amazing’ treasures revealed in Dartmoor bronze age cist and Legendary Dartmoor: Whitehorse Kirst ] . With the archaeological findings, you create an imagined history and mythology which is wondrous in the way it transcends the span of millennia, and offers something for us all – the miracle of what we share – even over such great stretches of time

3 — REBECCA: Well, there is no story or legend about this burial of a prestigious person on one of the highest spots on Dartmoor, overlooking the sources of at least three important rivers. I suppose you could say I tried to revivify whatever legend that must have faded out of collective memory long ago. I imagined what it might have been by looking at the evidence of the several wonderful artefacts that were found in the kystvaen (beads, bearskin, pollen) and at the actual location and made it all up. Later, I walked up to the windswept summit of White Horse Hill where I immediately realised that it really must have been an important ceremonial place. Perhaps people had made pilgrimages to the burial chamber, just as I had done. I privately read these poems in a whisper to the empty chamber and they felt right, as if I had brought a gift to honour her and they were accepted.

One of the poems from the Dartmoor Princess sequence:

On the dedication page of A Sprig of Rowan, Rebecca includes two lines from “A New Child” by Scottish poet George MacKay Brown

The stories, legends, poems

Will be woven to make your sail.

And with her poems in this pamphlet, Rebecca has continued the age-old tradition of these sorts of magic weaving, and I am glad she has.

What a wonderful informative interview and beautifully crafted poems. Folklore, myth, legend is bound in me and I know I have ‘strange ideas’ sometimes, (according to others) but all are linked to past beliefs. Hawthorn leaves in my pocket keep me safe and are taken from my own hawthorn. I hadn’t heard of the rowan’s powers but it is one I will remember and take with me. Thank you.

LikeLike

So glad to get your comments, Margaret 🙂 Perhaps however we do it, the thing is to somehow keep connections with what has gone before us. There is a beautiful old Mt. Ash in our back yard and I think now I will get a little bit of it for my backback and pocket … and a bit of hawthorn too … for good measure 🙂 x

LikeLike

Such a lot of care has gone into this interview – so informative. I have this pamphlet and have read it with new eyes after the answers to the perceptive and sensitive questions. Love the chosen poems – so representative of the rest – love all the mythology, the mystery and magic in all of these. Thank you both 🙂

LikeLike